No evidence for systematic voter fraud: A guide to statistical claims about the 2020 election

Edited

by Kenneth A. Shepsle, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved

August 30, 2021 (received for review February 22, 2021)

Significance

President

Donald Trump claimed that the 2020 US presidential election was stolen;

millions of Americans apparently believed him. We assess the most

prominent statistical claims offered by Trump and his allies as evidence

of election fraud, including claims about Dominion voting machines

switching votes from Trump to Biden, suspiciously high turnout in

Democratic strongholds, and the supposedly inexplicable failure of Biden

to win “bellwether counties.” We use a combination of statistical

reasoning and original data analysis to assess these claims. We hope our

analysis contributes to public discussion about the integrity of the

2020 election and broader challenges of election security and election

administration.

Abstract

After

the 2020 US presidential election Donald Trump refused to concede,

alleging widespread and unparalleled voter fraud. Trump’s supporters

deployed several statistical arguments in an attempt to cast doubt on

the result. Reviewing the most prominent of these statistical claims, we

conclude that none of them is even remotely convincing. The common

logic behind these claims is that, if the election were fairly

conducted, some feature of the observed 2020 election result would be

unlikely or impossible. In each case, we find that the purportedly

anomalous fact is either not a fact or not anomalous.

Sign up for PNAS alerts.

Get alerts for new articles, or get an alert when an article is cited.

Following

the 2020 US elections, President Trump and other Republicans questioned

Biden’s victory in public statements and lawsuits. Although Trump’s

legal challenges were unsuccessful, many of his supporters were

apparently convinced by his claims that the election was stolen: A

survey in December 2020 found that over 75% of Republican voters found

merit in claims that millions of fraudulent ballots were cast, voting

machines were manipulated, and thousands of votes were recorded for dead

people (1).

In

this paper, we consider several widely disseminated claims purporting

to call into question the 2020 US presidential election result. We focus

on statistical claims, i.e., claims that are based on allegedly

anomalous patterns in the official vote counts. The common logic of

these claims is that some aspect of the 2020 result would be highly

unlikely or even impossible if the election had been properly

administered. We performed an extensive search to identify the most

pervasive such claims appearing in social media posts, expert witness

testimony, and research papers.*

Our purpose in this paper is to address several of the most pervasive

statistical claims in one place and using a common conceptual framework.

We

conclude that each of the statistical claims we consider fails in one

of two ways. In some instances, accurate claims are made about the

election results but they are not actually inconsistent with a free and

fair election. In other instances, the supposedly anomalous fact about

the 2020 election result turns out to be incorrect.

The

2020 election was remarkable in many ways (e.g., unusually high levels

of mail-in voting and turnout), and election administration may well

have been imperfect. But we see nothing in these statistical tests that

supports Trump’s claim of a stolen election.

This research builds on efforts to assess the prevalence of fraud in prior elections in the United States (2 –4) and other democracies (5).

We also work in parallel with a large number of legal briefs filed by

political science experts after the 2020 election (for example, refs. 6 and 7).

Claims Based on Facts That Are Not Actually Anomalous

Biden’s Share of US Counties Is Not Anomalous

Conservative

radio talk show host Charlie Kirk tweeted on 20 December 2020, “Does

anyone else have a hard time believing Joe Biden won a record-high

number of votes despite winning a record-low number of counties?Ӡ

Later that day, he provided numbers to back up the claim, stating that

Barack Obama won 69 million votes and 873 counties (in 2008) and Donald

Trump won 74 million votes and 2,497 counties (in 2020), while Biden won

81 million votes and just 477 counties (also in 2020).‡

While Kirk understated the number of counties Biden won (537, not 477),

the basic fact is correct: Biden won far more votes than Trump or Obama

while winning far fewer counties than Trump and somewhat fewer counties

than Obama.§ If Biden won so few counties, how could he have legitimately won so many votes?¶

Adding

minimal context to Kirk’s numbers reveals that there is nothing

remotely suspicious or even anomalous about them. The reason Biden won a

clear majority of votes while winning a minority of counties is that

his support was concentrated in populous counties. This is typical of

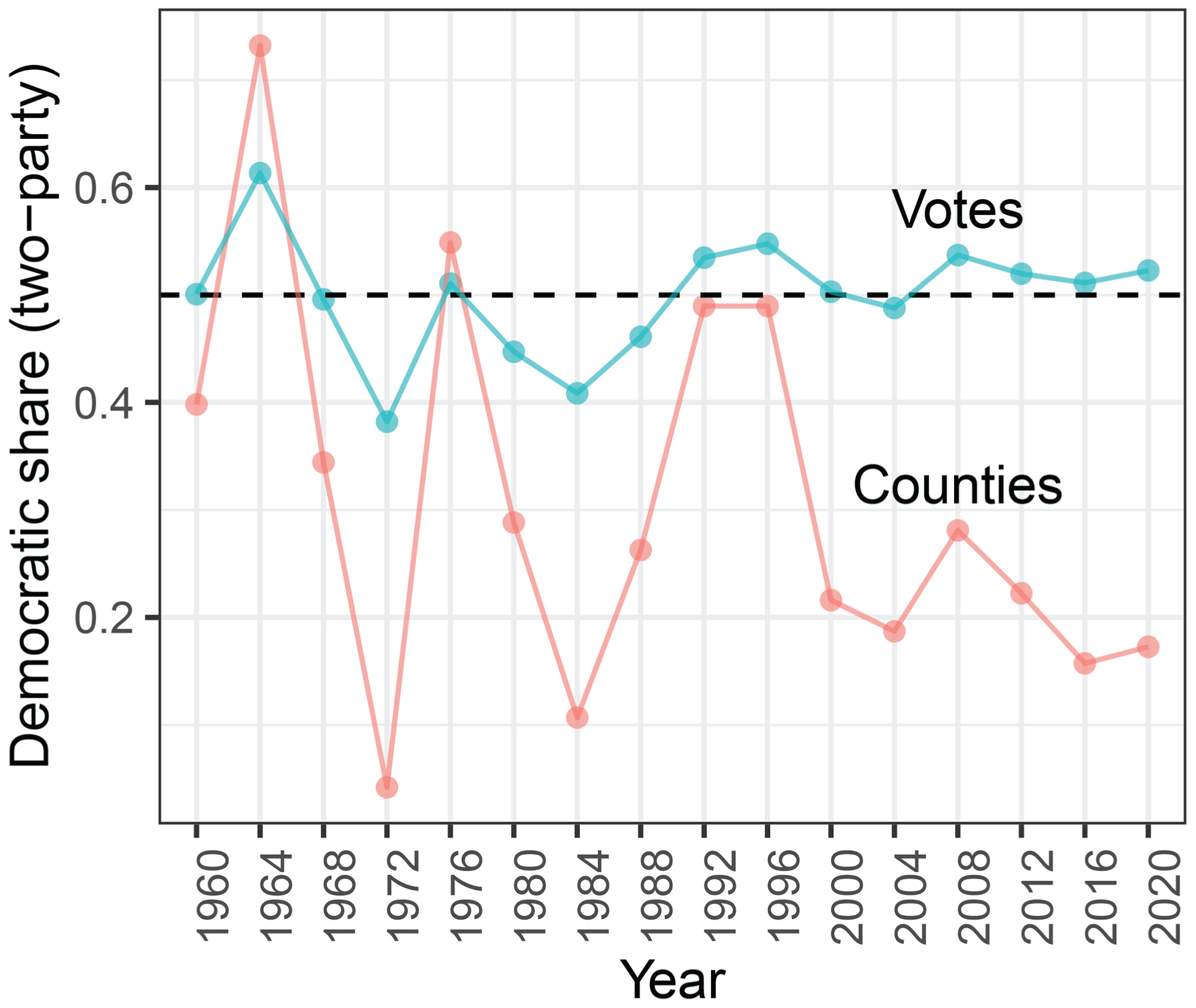

recent Democratic presidential candidates. Fig. 1

shows the proportion of votes and counties won by Democratic

presidential candidates over the last several decades. As Democratic

support has become more concentrated in cities, Democratic candidates

have tended to win a smaller share of counties even as their share of

votes holds steady. Judging by both votes and counties, Biden did

slightly better than Hillary Clinton in 2016 and worse than Obama in

2008. (Biden won many more votes than Obama, as Kirk pointed out, but a

smaller share of votes; turnout in 2020 was extraordinarily high.) Thus,

the supposedly incredible discrepancy Charlie Kirk highlighted is

simply the continuation of a stable trend in US presidential elections.

Fig. 1

Biden’s Share of Bellwether Counties Is Not Anomalous

A

related claim was made about Biden’s performance in “bellwether”

counties, which are counties where a majority of voters have supported

the election winner in several consecutive elections (8, 9).

Of the 19 counties that voted for the eventual winner in every

presidential election from 1980 to 2016, Biden defeated Trump in only

one. Several commentators viewed this fact as anomalous. As stated in The Federalist,

“Amazingly, [Biden] managed to secure victory while also losing in

almost every bellwether county across the country. No presidential

candidate has been capable of such electoral jujitsu until now” (10). Trump recited this fact in a rally in Georgia (11).

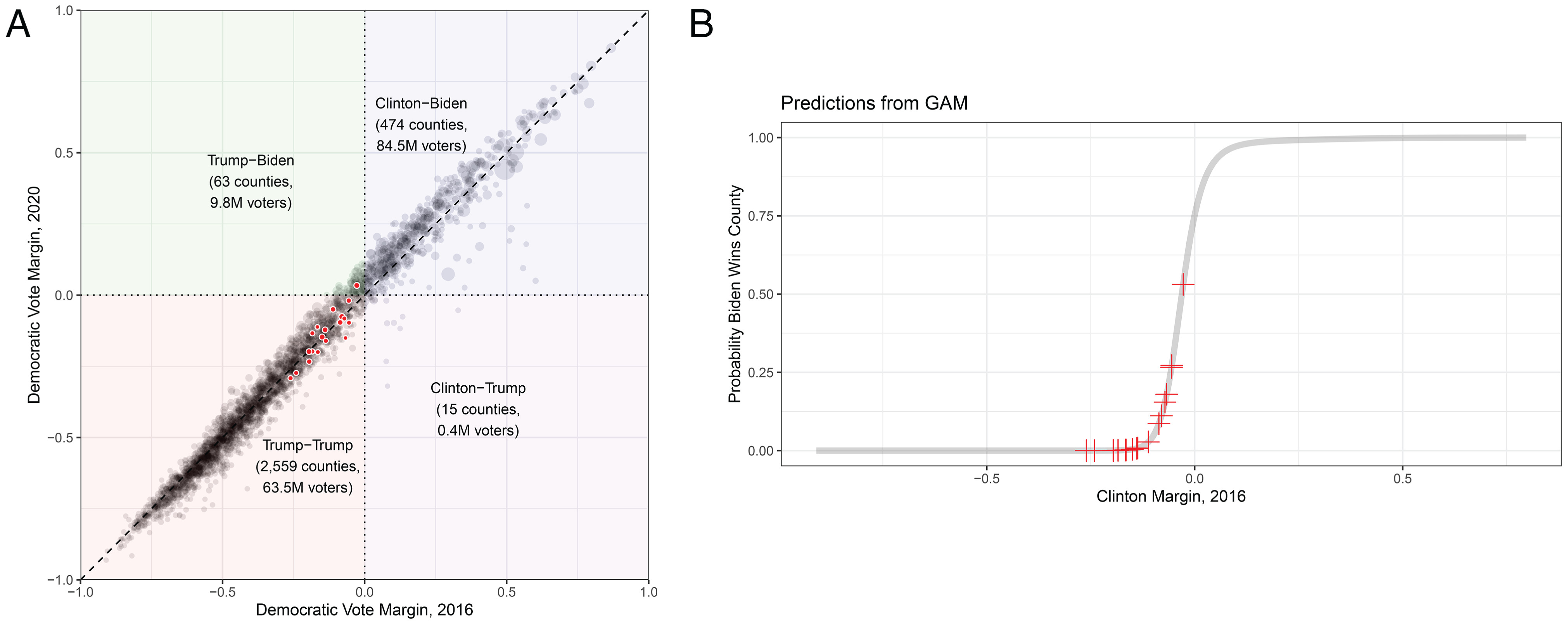

Biden’s

poor performance in bellwether counties makes sense given two facts.

First, at the county level there was remarkable continuity between 2016

and 2020.# Not only did Biden win roughly the same proportion of counties as Clinton in 2016 (as shown in Fig. 1), but also he won almost the same set of counties: As shown in Fig. 2A

only 63 counties switched from Trump to Biden. (For each county, we

show Democratic vote margin in 2016 on the horizontal axis and in 2020

on the vertical.) The 19 bellwether counties are highlighted in red.

Visual inspection suggests that, like other counties, they voted in 2020

roughly as they did in 2016; given this (and given that many of these

counties went solidly for Trump in 2016), it is unsurprising that Biden

won only one of them. Indeed, if we model the probability of Biden

winning a county as a function of the county’s Democratic margin in 2016

(making no distinction between bellwethers and others), we find that

Biden would be expected to win between one and two bellwethers. Fig. 2B

shows the probability of Biden winning a county in 2020 given the 2016

Democratic margin in the county, with the conditional relationship

calculated using a generalized additive model. The expected number of

bellwethers won by Biden is just 1.65 under this model; with alternative

models we get estimates between 1.2 and 1.8.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2A suggests, and the analysis in Fig. 2B

assumes, that bellwether counties have no special tendency to side with

the winner, conditional on the prior election result. Further analysis

indicates that this has long been the case (8).

To assess whether bellwethers are more likely than other counties to

side with the winner in the future, we analyzed each election since

1996. We modeled a county’s probability of correctly choosing the winner

in a given election as a function of the Democratic margin in the

county in the previous election and an indicator for whether the county

had sided with the winner in each past election since 1980. We find only

one election since 1996 in which bellwethers were more likely to side

with the winner than other counties conditional on the county’s previous

election result (SI Appendix, Fig. 1).

Considering

that bellwether counties appear to have no special prognostic value in

general, and that county-level results were very similar in 2020 and

2016, it is neither surprising nor suspicious that Biden won just one of

19 bellwethers in 2020.

Differences between 2016 and 2020 Are Not Anomalous

Trump

advocates argued on the basis of a statistical analysis that there was a

“one-in-a-quadrillion” chance that Joe Biden legitimately won the

election. This claim comes from an expert report submitted as part of

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s lawsuit against the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania. In that report (12),

Paxton claims that the expert, Charles Cicchetti, calculated a one-

in-a-quadrillion chance of Biden winning; Cicchetti concludes his report

by arguing that “In my opinion, the outcome of Biden winning

Cicchetti’s assertion

that Biden’s victory was “statistically improbable” is based on a deeply

misguided application of null hypothesis significance testing.

Cicchetti never actually computes the probability of Biden winning.

Instead, he tests the null hypothesis that Joe Biden in 2020 and Hillary

Clinton in 2016 had the same expected number of votes in particular

states.‖

But if the objective is to assess whether Biden won legitimately, then

it is beside the point whether Biden and Clinton enjoyed the same

expected support. Support can differ across candidates for any number of

reasons, and it is absurd to think that any such difference constitutes

evidence of election fraud.

More

specifically, Cicchetti treats the number of Democratic votes in an

election as a binomially distributed random variable and tests the

hypothesis that the expected number of Democratic votes (e.g., in

Arizona) was the same for Joe Biden in 2020 as it was for Hillary

Clinton in 2016. Let

For

example, Biden won 0.494 of 3.33 million votes in Arizona in 2020,

while Clinton won 0.446 of 2.41 million votes in Arizona in 2016; this

yields z = 477.09, for a P value very close to zero. Given

that Biden won a substantially larger share of a much larger total, it

should not be surprising that we soundly reject the null hypothesis that

the two candidates had the same expected vote total. But it is

preposterous to attribute that difference to fraud rather than the

myriad innocuous differences between the two elections. It would be

similarly preposterous to conclude that something was suspicious about

TV ratings because fewer people watched the Super Bowl in 2020 than in

2016 (z statistic: 1,495) or to suspect foul play in COVID-19

vaccine trials because the number of infected participants differs

between two trials using different vaccines on different numbers of

participants.

To further highlight the

absurdity of Cicchetti’s test, we applied it to other years and states

since 1960. Unsurprisingly, we nearly always reject the null hypothesis

(1,488 state–year combinations of 1,498). By Cicchetti’s logic, this

suggests that fraud is commonplace across nearly all US states and

elections. In fact, the test indicates simply that elections differ from

each other, an unsurprising conclusion that tells us nothing about

fraud.

Patterns of Straight-Ticket and Split-Ticket Voting in Michigan Not Anomalous

In

a YouTube video with over 1 million views, Shiva Ayyadurai claimed to

provide evidence that voting machines in Michigan decisively switched

votes from Trump to Biden (13).

The analysis compares Trump’s share of straight-ticket votes and

Trump’s share of split-ticket votes across precincts in four Michigan

counties. (Voters in Michigan can tick a single box to vote straight

ticket for all candidates of one party or vote split ticket for

individual candidates.) Ayyadurai argues that, if ballots were counted

properly, the difference between those two proportions in a precinct

should be unrelated to Trump’s success among straight-ticket voters in

that precinct. In the four counties he analyzes, Ayyadurai finds instead

a negative linear relationship, which he interprets as evidence that

Biden stole votes from Trump.

Ayyadurai’s

argument has been debunked by others, including two analysts who point

out that the same logic would also imply that Trump stole votes from

Biden in the same counties (14, 15).

We show that the negative relationship Ayyadurai takes as evidence of

fraud is an expected consequence of regression to the mean and that the

same pattern should be found when fraud is absent.

Let Xi and Yi denote Trump’s share of straight-ticket votes and split-ticket votes in precinct i, respectively. Ayyadurai’s observation is then that

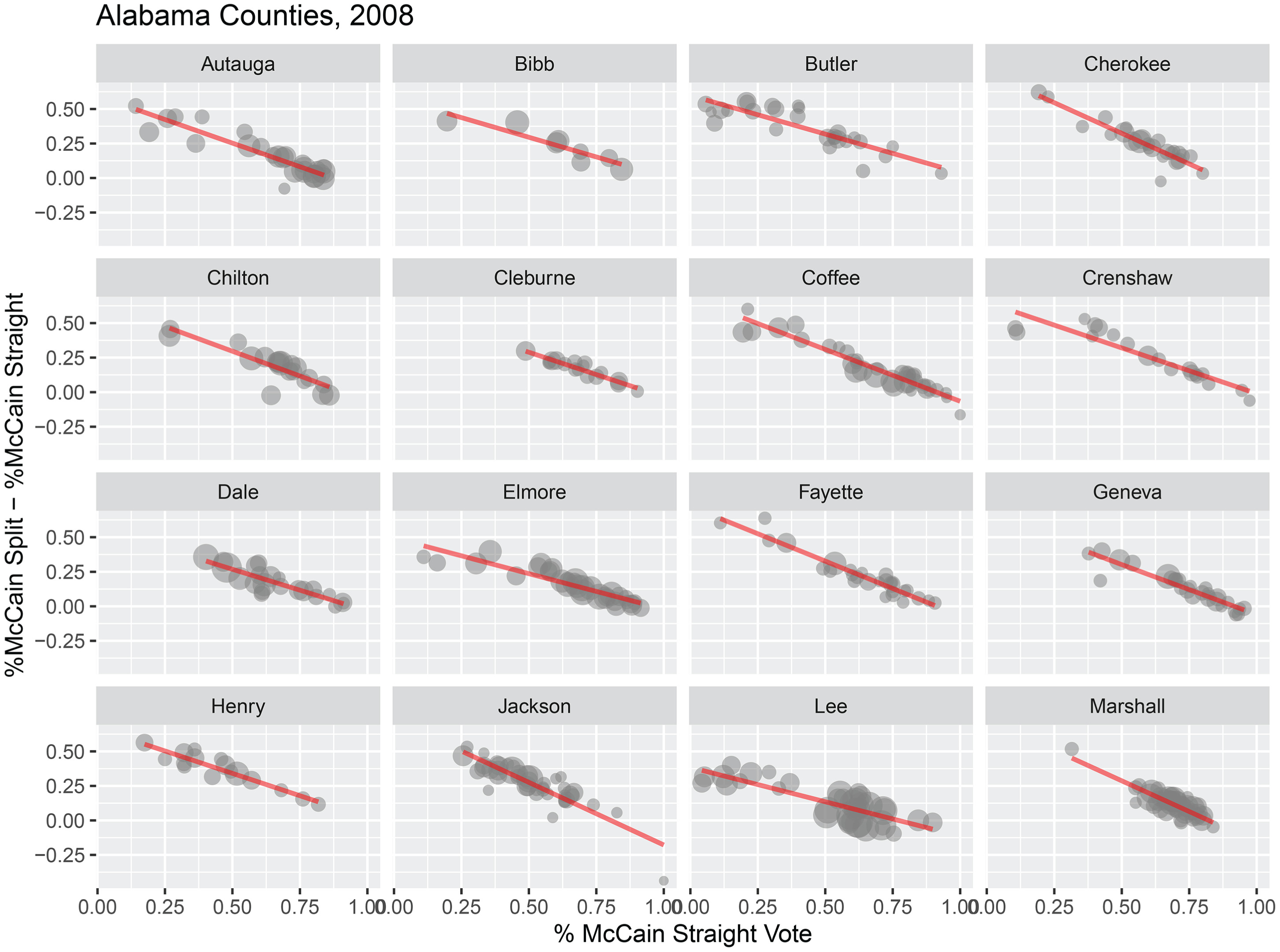

This

suggests that we should find Ayyadurai’s negative relationship in other

elections in which voters may vote straight ticket or split ticket and

fraud is not suspected. Conveniently, in a follow-up video Ayyadurai

points out that the 2008 presidential election in Alabama was just such

an election (16).

We therefore check the 2008 Alabama election returns for patterns like

the one Ayyadurai observes in Michigan in 2020. As expected, many

Alabama counties exhibit precisely the negative relationship in 2008

that Ayyadurai considers evidence of fraud in Michigan counties in 2020,

as shown in Fig. 3. (Each dot is a precinct,

scaled by the number of votes cast in the precinct; the red line is the

linear prediction.) This confirms that the relationship Ayyadurai

highlights is a feature of normal elections and not proof of fraud. In SI Appendix, Fig. 3

we show that in 32 of 35 Alabama counties the slope coefficient from a

regression of McCain’s split-ticket share on his straight-ticket share

is less than 1, and in 29 of those counties we reject the null that the

slope is 1.

Fig. 3

Claims Based on Facts That Are Not Actually Facts

Dominion Voting Machines Do Not Decrease Trump Vote Share

Trump’s

legal team claimed after the election that voting machines run by

Dominion Voting Systems switched votes from Trump to Biden. Trump

lawyers Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell argued for a global conspiracy

that undermined democracy everywhere Dominion was present. In late

December, an anonymous analysis was widely circulated on social media

claiming to show that Biden outperformed expectations in counties that

used Dominion voting machines (17). The right-wing news outlet The Epoch Times

reported that the analysis showed Biden outperformed expectations in

78% of the counties that use Dominion or Hart voting machines and that

the analysis “also indicates that Biden consistently received 5.6

percent more votes in those counties than he should have” (18).

Assessing whether a particular set of voting machines caused Biden to

receive more votes is difficult, because machines are not randomly

assigned to counties (19). Further, in SI Appendix, section E we present analyses indicating that the original study was the result of P hacking and careless data analysis.

Given

these problems with the original analysis, we carry out our own

analysis to check for evidence that Dominion machines switched votes

from Trump to Biden. In Table 1, column 1 we show the

results of a bivariate regression of Biden’s share in 2020 on an

indicator for whether the county used a Dominion machine, finding a very

slight and statistically insignificant difference. In Table 1, column 2 we adjust for Clinton’s share of the vote in 2016, which strongly predicts the 2020 outcome (note the R 2 of 0.964); the Dominion coefficient becomes very slightly negative, although again it is not significant. In Table 1, column 3 we add a dummy variable indicating whether the county is in a state where any Dominion machines were used and in Table 1,

column 4 we add a fixed effect for each state; in both cases we find

coefficients that are statistically significant in the negative (i.e.,

pro-Trump) direction, although very small in magnitude. In Table 1

we find the same null effect of Dominion voting machines persists

regardless of how we classify a county as using Dominion machines, once

we account for confounding at the state level and for county-level

demographics. In short, using the most rigorous specifications we find

no evidence that Biden outperformed expectations in counties where

Dominion machines were used.

Table 1

| Dependent variable: Biden vote share, 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Dominion machines | 0.007 | –0.002 | –0.009 | –0.006 |

| (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Clinton share of vote, 2016 | 1.032 | 1.029 | 1.011 | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | ||

| Observations | 3,111 | 3,111 | 3,111 | 3,111 |

| R 2 | 0.0002 | 0.964 | 0.965 | 0.975 |

| Dummy for “Dominion state” | ✓ | |||

| State fixed effects | ✓ | |||

Data

from all states and the coding of Dominion voting systems from the US

Election Assistance Commission are used. SEs in parentheses.

Absentee Ballot Counting Procedures Do Not Decrease Trump Vote Share

Another

focus of the Trump team’s accusations was the processing of absentee

ballots in key states that Biden narrowly won. Among other claims, they

alleged that Fulton County, GA, and Allegheny County, PA, were major

centers of voter fraud in the 2020 election. Most of these allegations

relied upon hearsay affidavits or debunked videos purportedly showing

voters stuffing ballots. But in a paper posted in late December 2020,

Lott (20)

claims to provide statistical evidence that irregularities in the

absentee vote counting procedure in Fulton County and Allegheny County

suppressed votes for Trump and bolstered Biden’s vote count. Lott

examined precincts along the border of Fulton and Allegheny Counties and

argued that he detected anomalous support for Biden in his absentee

ballot share relative to his in-person share of ballots in Fulton and

Allegheny Counties. Lott’s paper received immediate and widespread

attention. Peter Navarro, Assistant to the President and Director of the

Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, touted the claim as solid

evidence of fraud. President Trump tweeted out a link to the paper.

Lott’s claims, however, do not withstand scrutiny. Using Lott’s own data, we show in SI Appendix, section G

that the specification he uses to analyze absentee voting patterns

produces different conclusions depending on the entirely arbitrary order

in which counties are entered in the dataset. Briefly, Lott posits

that, if absentee ballots were correctly handled, the difference in

Trump support across a boundary that separates a Democratic county from a

Republican county should be similar to the difference in Trump support

across a boundary that separates one Republican county from another. But

Lott’s conclusion depends entirely on the order in which the

differences are computed for the Republican–Republican pairs. The

conclusion is reversed when an alternative and equally justified order

is used.

To achieve Lott’s objective of

comparing voting patterns across county boundaries, we reanalyze Lott’s

data using a more standard specification that does not suffer from these

problems. We use the same pairs of precincts that Lott (20)

used in his analysis to limit the confounding between precincts in

different counties, but we now use a simple fixed-effects model that

resolves the issue with Lott’s (20) original specification. The regression equation for this model can be written as

[1]

Table 2

| Dependent variable: Trump share absentee | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia | Pennsylvania | |||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Trump share, in person | 0.760 | 0.606 | 0.511 | 0.307 |

| (0.049) | (0.077) | (0.042) | (0.066) | |

| Suspect county | 0.019 | –0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| Observations | 44 | 44 | 174 | 174 |

| Precinct-pair fixed effects | ✓ | ✓ | ||

A

fixed-effects specification shows nothing suspicious in Fulton County,

GA, and nothing suspicious in Allegheny County, PA. SEs in parentheses.

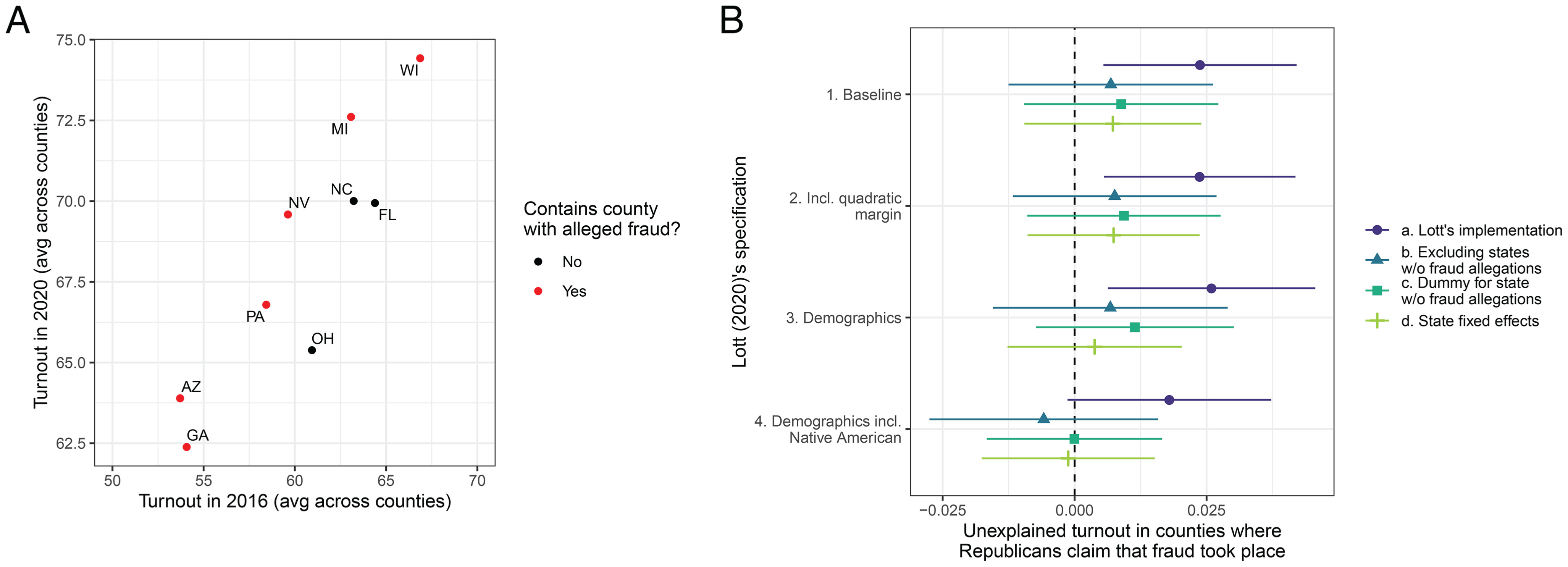

Turnout Was Not Unusually High in Counties Where Republicans Made Fraud Accusations

Lott (20)

also claims to show that 2020 turnout rates were higher than one would

otherwise expect in a set of counties where Republicans have alleged

that fraud took place. Lott argues that there was an “unexplained

increase in voter turnout” ref. 20, p.13 in the key counties of between

1.26 and 2.42%, which Lott says is equivalent to 150,000 to 289,000

votes in those states. Lott concludes that this is evidence consistent

with fraud.

To determine whether the

“suspicious” counties had higher turnout, Lott checks whether turnout in

the 2020 election was higher than would be expected (given previous

turnout, political leaning, and local demographics) in counties where,

according to Republican lawsuits filed after the election, fraud may

have taken place. Lott identifies 19 counties across six swing states

where Republicans made fraud allegations.††

He then compares turnout in these counties to turnout in other counties

in the same six states plus all counties in three other swing states

(Florida, Ohio, and North Carolina). He argues that, if turnout is

higher in these counties than would be expected given covariates, it

would be evidence of fraud.

As we explain in SI Appendix, section H

we dispute the premise of this analysis: Turnout varies across counties

for many reasons, and it is unreasonable to ascribe a small unexplained

difference to fraud. As it happens, Lott’s finding is not robust to

sensible departures from his chosen specification, so it is not

necessary to dispute the premise.

Our analysis of county-level voting data for 2016 and 2020‡‡

indicates that Lott’s conclusions are driven by the inclusion of states

that have lower turnout increases and no suspicious counties—namely

Florida, North Carolina, and Ohio. Fig. 4A

shows that, conditional on turnout in 2016, turnout in these three

states was lower than turnout in the six states that contain a

suspicious county in Lott’s analysis. This is relevant because Lott’s

analysis compares changes in turnout in suspicious counties with changes

in turnout in all other counties, so these smaller increases in turnout

rates across states will be conflated with the suspicious county

indicator in his analysis. The smaller the turnout increase in these

three “nonsuspect” states, the more turnout in the suspect counties will

appear to be suspiciously high, even if the changes in turnout in these

suspect counties are unremarkable relative to the changes in turnout in

other counties in their own state.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4B shows that, once we address the level differences across states, Lott’s (20)

estimates of the turnout differences in suspicious counties go to zero

and become insignificant. We examine all four of Lott’s (20)

models (organized on the vertical axis) and present the estimated

coefficient on an indicator for “suspicious county” in a regression of

2020 turnout on that indicator plus 2016 turnout and covariates. The

circle/purple estimates of suspicious county turnout depict the

estimates using the four specifications for which Lott (20)

presents results in his table 10. The triangle/dark-green estimates

depict our estimates when we exclude Florida, Ohio, and North

Carolina—three states in which no fraud was alleged. Across models, the

difference in suspicious counties is close to zero and—in the case of

model 4—the estimate is negative. The square/light-green estimates are

from a model where we include all of Lott’s states but add an indicator

for a state that has suspicious counties. Again, this reduces the

estimate to null. Finally, the last estimates (plus/lime green) include

state-level fixed effects. Across models, this gives a close to zero and

null difference for suspicious counties. Thus, simply by focusing only

on states where at least one county had alleged fraud (i.e., swing

states that Biden won) or allowing that state-wide turnout trends may

differ across states or groups of states, we are able to explain what

Lott (20) claimed was unexplained turnout in counties where Republicans had claimed fraud.

In

short, there is no evidence that turnout was unusually high in the

suspicious counties, let alone that turnout was inflated in these

counties by fraud.

Statistical Analyses of Elections, the Detection of Fraud, and the Spread of Misinformation

Even

though the 2020 election is over and Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn

the results failed, the effects of the claims will reverberate for

years. A large segment of the public remains skeptical that Biden won

the election legitimately and Republican state lawmakers are taking

steps to alter voting access in the name of preventing fraud. The Trump

campaign delivered a blueprint for losing candidates to undermine

support for the winner or even steal the election. It seems unlikely

that he will be the last to try these tactics.

We

have closely examined what we consider the most prominent statistical

claims of fraud in the 2020 election. Although the claims are diverse,

our conclusion is consistent: For each claim, we find that what is

purported to be an anomalous fact about the election result is either

not a fact or not anomalous. In many cases the alleged fact, if shown to

withstand scrutiny, would hardly constitute convincing evidence that

Biden was elected due to fraud: A modest advantage to Biden in counties

that chose to use Dominion machines, for example, could be explained by

chance, by factors not accounted for in statistical models, or indeed by

pro-Trump fraud undertaken using other voting machines. As it happens,

the allegedly anomalous features we consider appear mundane once

properly measured or placed in the appropriate context.

In

some cases, members of the public who are confronted with a statistical

claim of election fraud can apply the approach we took in this paper:

First, ask whether the allegedly anomalous fact is a fact; if so, ask

whether it is anomalous. In many cases, assessing the validity and

unexpectedness of an allegedly anomalous fact requires some statistical

sophistication and even original data analysis. For these cases, we

think academics (and data journalists and others with appropriate

skills) have an important role to play. To safeguard future election

results, it will be essential to have elections experts ready to

evaluate claims made about whether an election is free and fair. We

think that social media organizations can do more to broadcast these

evidence-based claims rather than merely flagging questionable

assertions as disputed or asserting that the election was free and fair.

Rebuilding

trust in American elections requires that we fairly evaluate claims

about their failures and communicate those claims to a skeptical public.

This paper is an effort in that direction.

Notes

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

*

SI Appendix, section A describes our search process.

§

By “counties” we mean counties and county equivalents, e.g., parishes in Louisiana.

¶

Turning

Kirk’s question around, one could ask, If Trump won so few votes, how

could he have legitimately won so many counties? The same point could be

made for many of these claims.

#

SI Appendix, Fig. 2 shows that the serial correlation in county-level election results has increased steadily to a new high in 2020.

‖

He

also tests the hypothesis that Biden’s early and late vote counts were

the same in specific states. This test is subject to the same critique,

which we show in SI Appendix, section D.

**

To see this, suppose that underlying Trump support is given by Ti and that

††

Lott

identifies the following suspicious counties—in Georgia, Fulton and

DeKalb; in Pennsylvania, Allegheny, Centre, Chester, Delaware,

Montgomery, Northampton, and Philadelphia; in Arizona, Apache, Coconino,

Maricopa, and Navajo; in Michigan, Wayne; in Nevada, Clark and Washoe;

and in Wisconsin, Dane.

‡‡

We

use turnout rates for the county citizen voting-age population. For the

number of voting-aged citizens we use the 5-y American Community Survey

from 2019 and 2015. This follows best practice from McDonald (21). For total votes, we use Leip (22). We note that our estimates of turnout are lower than Lott’s (20) average turnout rates, but closer to official statistics.

Data Availability

Election results data have been deposited in Code Ocean at https://codeocean.com/capsule/0007435/tree/v2.

Supporting Information

Appendix 01 (PDF)

- Download

- 931.90 KB

References

1

J.

Zilinsky, J. Nagler, J. Tucker, Which Republicans are most likely to

think the election was stolen? Those who dislike democrats and don’t

mind white nationalists. Washington Post, 19 January 2021. https://

www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/19/which-republicans-think-

election-was-stolen-those-who-hate-democrats-dont-mind-white-

nationalists. Accessed 19 January 2021.

2

D.

Cottrell, M. C. Herron, S. J. Westwood, An exploration of Donald

Trump’s allegations of massive voter fraud in the 2016 general election.

Elect. Stud. 51, 123–142 (2018).

3

M. C. Herron, Mail-in absentee ballot anomalies in North Carolina’s 9th congressional district. Elect. Law J. Rules Polit. Policy 18, 191–213 (2019).

4

W. R. Mebane, Comment on “Benford’s law and the detection of election fraud”. Polit. Anal. 19, 269–272 (2011).

5

N. Idrobo, D. Kronick, F. Rodríguez, Do Shifts in Late-Counted Votes Signal Fraud? Evidence from Bolivia (University of Pennsylvania, 2020).

6

J. Rodden, Expert report of Jonathan Rodden, PhD in Pearson v. Kemp. https://1library.net/document/qm8mlnwz-december-pearson-united-states-district-northern-district-georgia.html. Accessed 20 October 2021.

7

G. King, Expert report of Gary King, in Bowyer et al. v. Ducey (governor) et al., US district court, district of Arizona. https://gking.harvard.edu/publications/expert-report-gary-king-bowyer-et-al-v-ducey-governor-et-al-us-district-court. Accessed 20 October 2021.

8

E. R. Tufte, R. A. Sun, Are there bellwether electoral districts? Public Opin. Q. 39, 1–18 (1975).

9

D. Zimny-Schmitt, M. Harris, An inquiry of bellwether counties in US presidential elections. SSRN [Preprint] (2020). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3677602. Accessed 20 October 2021.

10

J. Shurk, 5 more ways Joe Biden magically outperformed election norms. The Federalist, 23 November 2020. https://thefederalist.com/2020/11/23/5-more-ways-joe-biden-magically-outperformed-election-norms/. Accessed 7 December 2020.

11

P. Bump, No, Biden’s win wasn’t ‘statistically impossible.’ Washington Post, 7 December 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/12/07/no-bidens-win-wasnt-statistically-. Accessed 1 December 2020.

12

C. Cicchetti, Expert report of Charles Cicchetti in Texas vs Pennsylvania. https://electioncases.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/TX-v-PA-Appendix-first-half.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2020.

13

S.

Ayyadurai, “Dr. Shiva live: MIT PhD analysis of Michigan votes reveals

unfortunate truth of US voting systems” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ztu5Y5obWPk. Accessed 10 February 2021.

14

N. Kabir, The fraud of Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai: Oakland county, Michigan. https://naim-kabir.medium.com/the-fraud-of-dr-shiva-ayyadurai-oakland-county-michigan-1bc51bcebf1b. Accessed 10 February 2021.

15

M. Parker, “Do these scatter plots reveal fraudulent vote-switching in Michigan?” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aokNwKx7gM8. Accessed 10 February 2021.

16

S.

Ayyadurai, “Dr. Shiva live: MIT PhD continued analysis of Michigan

votes reveals more election fraud” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8xb6qJKJqU&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 10 February 2021.

17

Anonymous, Evidence of fraud in conjunction with use of dominion BMD machines. https://thepartyoftrump.com/media/FraudInCountiesUsingDominionVotingMachines.pdf. Accessed 10 January 2021.

18

A. Zhong, Joe Biden appears to outperform in counties using dominion or hart voting machines: Data analyst. Epoch Times, 19 December 2020. https://

www.theepochtimes.com/joe-biden-appears-to-outperform-in-counties-using-

dominion-or-hart-voting-machines-data-analyst_3625672.html. Accessed 10 January 2021.

19

M. C. Herron, J. Wand, Assessing partisan bias in voting technology: The case of the 2004 New Hampshire recount. Elect. Stud. 26, 247–261 (2007).

20

J.

R. Lott, A simple test for the extent of vote fraud with absentee

ballots in the 2020 presidential election: Georgia and Pennsylvania

data. SSRN [Preprint] (2020). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3756988. Accessed 20 October 2021.

21

M. McDonald, I want congressional, state legislative district, or county VEP turnout rates. http://www.electproject.org/home/voter-turnout/faq/congress. Accessed 15 January 2021.

22

D. Leip, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. https://uselectionatlas.org/. Accessed 20 October 2021.

Information & Authors

Information

Published in

Classifications

Copyright

Copyright © 2021 the Author(s). Published by PNAS. This open access article is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

Data Availability

Election results data have been deposited in Code Ocean at https://codeocean.com/capsule/0007435/tree/v2.

Submission history

Accepted: August 30, 2021

Published online: November 2, 2021

Published in issue: November 9, 2021

Keywords

Notes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Authors

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Altmetrics

Citations

Cite this article

No evidence for systematic voter fraud: A guide to statistical claims about the 2020 election, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

118 (45) e2103619118,

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2103619118

(2021).

Copied!

Copying failed.

Export the article citation data by selecting a format from the list below and clicking Export.

Cited by

Loading...

View Options

Figures

Fig. 1

Biden’s share of votes and counties won in 2020 is typical of that of recent Democratic presidential candidates.

Fig. 2

A

plot shows Democratic vote margin in 2016 (horizontal axis) and 2020

(vertical axis) by county: Support in most counties did not shift much,

and bellwethers (colored red) were no exception. B plot

calculates the expected share of counties Biden won given the 2016

Democratic margin. Trump’s margin in bellwether counties (red plus) was

large and Biden won only a small share of those. We use several flexible

models to calculate Biden’s expected number of bellwether county wins

if they behave like other counties and we find that Biden would be

expected win between 1.24 and 1.75 bellwethers.

Fig. 3

Several

counties in Alabama in 2008 show the same relationship between

split-ticket voting and straight-ticket voting that Ayyadurai interprets

as evidence of fraud in Michigan in 2020.

Fig. 4

Tables

Media

References

References

1

J.

Zilinsky, J. Nagler, J. Tucker, Which Republicans are most likely to

think the election was stolen? Those who dislike democrats and don’t

mind white nationalists. Washington Post, 19 January 2021. https://

www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/19/which-republicans-think-

election-was-stolen-those-who-hate-democrats-dont-mind-white-

nationalists. Accessed 19 January 2021.

2

D.

Cottrell, M. C. Herron, S. J. Westwood, An exploration of Donald

Trump’s allegations of massive voter fraud in the 2016 general election.

Elect. Stud. 51, 123–142 (2018).

3

M. C. Herron, Mail-in absentee ballot anomalies in North Carolina’s 9th congressional district. Elect. Law J. Rules Polit. Policy 18, 191–213 (2019).

4

W. R. Mebane, Comment on “Benford’s law and the detection of election fraud”. Polit. Anal. 19, 269–272 (2011).

5

N. Idrobo, D. Kronick, F. Rodríguez, Do Shifts in Late-Counted Votes Signal Fraud? Evidence from Bolivia (University of Pennsylvania, 2020).

6

J. Rodden, Expert report of Jonathan Rodden, PhD in Pearson v. Kemp. https://1library.net/document/qm8mlnwz-december-pearson-united-states-district-northern-district-georgia.html. Accessed 20 October 2021.

7

G. King, Expert report of Gary King, in Bowyer et al. v. Ducey (governor) et al., US district court, district of Arizona. https://gking.harvard.edu/publications/expert-report-gary-king-bowyer-et-al-v-ducey-governor-et-al-us-district-court. Accessed 20 October 2021.

8

E. R. Tufte, R. A. Sun, Are there bellwether electoral districts? Public Opin. Q. 39, 1–18 (1975).

9

D. Zimny-Schmitt, M. Harris, An inquiry of bellwether counties in US presidential elections. SSRN [Preprint] (2020). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3677602. Accessed 20 October 2021.

10

J. Shurk, 5 more ways Joe Biden magically outperformed election norms. The Federalist, 23 November 2020. https://thefederalist.com/2020/11/23/5-more-ways-joe-biden-magically-outperformed-election-norms/. Accessed 7 December 2020.

11

P. Bump, No, Biden’s win wasn’t ‘statistically impossible.’ Washington Post, 7 December 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/12/07/no-bidens-win-wasnt-statistically-. Accessed 1 December 2020.

12

C. Cicchetti, Expert report of Charles Cicchetti in Texas vs Pennsylvania. https://electioncases.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/TX-v-PA-Appendix-first-half.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2020.

13

S.

Ayyadurai, “Dr. Shiva live: MIT PhD analysis of Michigan votes reveals

unfortunate truth of US voting systems” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ztu5Y5obWPk. Accessed 10 February 2021.

14

N. Kabir, The fraud of Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai: Oakland county, Michigan. https://naim-kabir.medium.com/the-fraud-of-dr-shiva-ayyadurai-oakland-county-michigan-1bc51bcebf1b. Accessed 10 February 2021.

15

M. Parker, “Do these scatter plots reveal fraudulent vote-switching in Michigan?” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aokNwKx7gM8. Accessed 10 February 2021.

16

S.

Ayyadurai, “Dr. Shiva live: MIT PhD continued analysis of Michigan

votes reveals more election fraud” (video recording, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8xb6qJKJqU&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 10 February 2021.

17

Anonymous, Evidence of fraud in conjunction with use of dominion BMD machines. https://thepartyoftrump.com/media/FraudInCountiesUsingDominionVotingMachines.pdf. Accessed 10 January 2021.

18

A. Zhong, Joe Biden appears to outperform in counties using dominion or hart voting machines: Data analyst. Epoch Times, 19 December 2020. https://

www.theepochtimes.com/joe-biden-appears-to-outperform-in-counties-using-

dominion-or-hart-voting-machines-data-analyst_3625672.html. Accessed 10 January 2021.

19

M. C. Herron, J. Wand, Assessing partisan bias in voting technology: The case of the 2004 New Hampshire recount. Elect. Stud. 26, 247–261 (2007).

20

J.

R. Lott, A simple test for the extent of vote fraud with absentee

ballots in the 2020 presidential election: Georgia and Pennsylvania

data. SSRN [Preprint] (2020). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3756988. Accessed 20 October 2021.

21

M. McDonald, I want congressional, state legislative district, or county VEP turnout rates. http://www.electproject.org/home/voter-turnout/faq/congress. Accessed 15 January 2021.

22

D. Leip, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. https://uselectionatlas.org/. Accessed 20 October 2021.